Play the Knave emerged at a time when performing artists around the world were exuberantly experimenting with mixed-reality technologies. In the zones of Shakespeare performance, perhaps the most significant of these experiments was the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 2016–2017 production of The Tempest. For this production, the actor playing Ariel wore a costume that operated as a controller for a digital projection. Ariel appeared on stage in the form of a human actor and, simultaneously, in the form of an animated avatar whose movements mirrored those of the human actor. To make all this possible, the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) collaborated with two companies on the cutting edge of entertainment technology: Intel, which makes the powerful processors that are so critical to gaming computers, and The Imaginarium Studios, a production facility cofounded by Andy Serkis, the actor who famously used motion-capture performance to bring the character of Gollum to life in The Lord of the Rings films.[1]

The choice to focus on The Tempest for this kind of collaborative theatrical experiment was so fitting, so predictable, that it had, in fact, been anticipated about 15 years earlier by another, much smaller theater company. David Saltz’s Interactive Performance Lab (IPL) at the University of Georgia used motion-capture technology to animate Ariel in its production of The Tempest. The directors of both productions have pointed out that The Tempest is a logical choice for high-tech experimentation because, throughout its long production history, the play has always challenged theater companies to use the latest and greatest technological wizardry to create illusions for the audience. Shakespeare’s First Folio includes a stage direction calling for “quaint devices” to be used to help the earliest Ariel perform his magical acts. So the interactive technology of motion capture (or mocap) is simply our present-day “quaint device.”[2]

Given that mocap has been used quite widely in contemporary performance, including in other Shakespeare productions, the RSC’s relatively late adoption of the technology is notable. Serkis offered this point by way of explanation: “We’ve always wanted to marry performance capture with the stage . . . But there are so many risks involved. There’s no room for error.”[3] Unlike films, video games, and video projections—the latter commonly used in Shakespeare performances by the RSC and many other companies—which can be recorded in advance and edited carefully before the audience sees them, the animation created in live mocap is rendered in real time. As we have explored in the prior acts from various angles, computers are not always great readers of human bodies. Live mocap is risky because if the performer moves in a way that the system cannot understand, the software receives confusing data, creating an animation that looks “glitchy.” The RSC and Intel invested huge sums of money and put in tremendous labor to lessen or eliminate glitchy animation in their momentous production of The Tempest. We argue that they did so at great ethical costs.

We shall examine those ethical costs by comparing the RSC’s heavily financed, corporate-driven mocap theater project with Play the Knave. In part because our team lacked the finances of Intel (to say the least!), but also because of the logic of our project’s design, users of Play the Knave frequently and repeatedly encounter glitches. As we have discussed, avatar glitchiness is arguably the predominant experience of playing the game. Instead of abjuring or apologizing for this “rough magic” (5.1.59), as Prospero does in The Tempest, we suggest here that the game’s glitches are at the center of its ethical promise.

As Play the Knave presents its users’ avatars as warped and even monstrous mirrors, the game puts pressure on the power dynamics that tend to inhere in relations between humans and digital technology.[4] Most of us see our relationship to technology as oppositional: either we feel we are being controlled by our technologies (why won’t my computer let me . . . ) and/or we pursue mastery over our technologies (I have figured out how to get my phone to . . .). Such power imbalances seem relatively innocuous only because we view our computers and phones as inert objects, differentiated and separated from our human bodies. But what if we take more seriously the view, discussed in prior acts, that human bodies are deeply entangled with digital technologies—an entanglement that motion-capture technology particularly underscores? In a posthuman world, how we perceive and treat digital objects is infused with ethical implications.[5] When we yell at our phones for not cooperating with our demands, for instance, we are practicing engagement with another entity, a nonhuman actor. Perhaps this might not seem to matter: phones aren’t alive; they don’t have feelings; they can’t be hurt by angry words. But, as The Tempest demonstrates so powerfully, the line between human and nonhuman can become blurry. Prospero feels comfortable commanding and mistreating Caliban and Ariel because he views them as nonhuman, as tools for service, like a phone. When we interact with our digital technologies, should we treat them the way Prospero treats Caliban? How do such interactions form patterns that we may bring to other interactions, with other others?

Play the Knave invites players to engage with the digital other in less ethically compromised ways. Because of the inherent glitchiness of the digital interface—a glitchiness that can be lessened but never eliminated, no matter what players may do—players of our game develop a more responsive and responsible relationship with the digital technology. They come to view the unruly digital other not as an antagonist that should or even can be controlled or managed, but rather as a partner with which to collaborate and from which to learn. Because players cannot master the digital other, they must either abandon the game or instead learn to accommodate the quirks of their uncanny digital doubles. In this manner, Play the Knave promotes a queer ethics of care, enticing players to enjoy the occasional graphic strangeness and embrace glitchiness.[6] As Trinculo realizes in The Tempest, “strange bedfellows” (2.2.41) can become quite welcome company.

We concur that The Tempest is an ideal play to perform using mocap technology, but not for the reasons the RSC cites—that is, not because mocap produces magical illusions for an audience. Rather, it is the riskiness of mocap and the tensions it creates between the body of the human player and the digital avatar that make it such a fascinating technology for thinking through The Tempest—the Shakespeare play that, perhaps more acutely than any other, stages a confrontation between human beings and nonhuman or abhuman creatures. Whereas the RSC’s mocap Shakespeare experiment celebrates the triumph of human over alien technology, Play the Knave uses Shakespeare to foreground our enmeshment with digital worlds and to expose the inherent glitchiness of the human body. As such, these two experiments with gaming technologies in the zones of Shakespeare performance open up very different interpretations of The Tempest.

“Would this monster make a man” | Human Actors vs. Digital Technology

It may seem rather unfair to characterize the RSC as having a monolithic attitude toward digital technology. The RSC is a large organization with many staff members, whose views of technology undoubtedly vary. But while we cannot know how individuals in the organization viewed mocap technology and its affordances in performance, we can examine how the relationship between human actors and digital technology were represented in the company’s official, public narratives surrounding their momentous production of The Tempest. For example, the RSC produced a series of behind-the-scenes, making-of videos to promote and create buzz around the project during the years leading up to the show; the RSC uploaded the videos to YouTube on March 24, 2017, presumably in anticipation of the show’s move to the Barbican on June 30, 2017. After the show closed, the RSC also released a glossy impact report titled Space to Play: Making Arts & Technology Collaborations Work. Written by Ceri Gorton, the co-director of the Bird & Gorton design consultancy, this impact report aimed to step back and assess the RSC’s collaboration with Intel in hopes of garnering lessons for the RSC and other arts organizations about partnering with technology companies. As the RSC’s Executive Director Catherine Mallyon puts it in her foreword to the report, “we want to take the opportunity to analyze what made this possible. To learn and to be confident that we can be as ambitious in the future.”[7] Presuming that the goal of the report and of the making-of videos was to convince the public—audiences, underwriters, and the like—about the project’s ultimate success, these materials cannot be taken completely at face value. In the end, they are public-relations media. Nevertheless, despite—or perhaps because of—their status as public-relations media, the videos and the report offer interesting insights into how the RSC as an organization perceived (or wanted the public to believe they perceived) the role of digital technology in cultural production.

One common motif in these media materials is that the RSC’s human actors approached the digital technology provided by Intel and The Imaginarium somewhat skeptically, seeing themselves in confrontation with a nonhuman other. The RSC’s impact report relates considerable anxieties about whether the human, theatrical world of the RSC could meld successfully with the tech world of Intel and The Imaginarium. While the report represents this collaboration on the whole as a partnership of equals, it also constantly reflects on the challenges involved. Mallyon notes the “different languages” the collaborators spoke, the “many questions” the RSC had, and the profound “uncertainty” they felt as they began working with Intel. The opening remarks in the report from Steve Fund, then Senior Vice President and Chief Marketing Officer at Intel, convey similar sentiments, recalling that “While the final production was flawless, the path to opening night took two years of testing, learning, and perfecting.”[8] One entire section of the report focuses on “Challenges,” and a consistent theme in this section is the RSC’s concern with preserving “quality.”[9] The RSC discovered through the project the need for a “culture shift”: “Enable risk, delegate and empower across hierarchies, provide time and space to play, and measure innovation beyond financial outputs.”[10] The long lead time to the production was meant to allow for “space to play,” space to explore and take risks. But, ultimately, the company and its technological partners could not afford any mistakes when the production was finally mounted. Their report admits that they held back on pursuing certain technological innovations in the name of “quality”: “A more technologically innovative or extensive intervention could have been possible, but not without compromising the audience’s experience, and the team’s ability to deliver consistently.”[11] The requirement of consistently high quality—what the RSC’s brand demands—led to “anxiety in the project team about deploying such new technology in a live event and not only once but 8 times a week for more than 2 months. This challenge of balancing the extent of innovation and creative ambition with the need for robustness and technical quality was addressed through testing, prioritising deliverability, and sticking to [Gregory] Doran’s ‘ruthless logic’ for the use of technology”—to wit, every idea that emerged during the R&D process had to be checked against Doran’s guiding question: “How is this enabling magic?”[12] The avatar rendering, in other words, had to be smooth so that audiences never saw the seams behind the illusion.[13] Notably, even as the report touts the production as a showcase collaboration of the tech and arts sectors—a collaboration that required both the RSC and its partners to make compromises—Doran is nevertheless presented as the final arbiter, ensuring that technology does not run the show.[14]

Overall, behind its celebratory rhetoric, the report betrays tensions between the RSC and its digital technology partners. The report quotes Sarah Ellis, the RSC’s Director of Digital Development and the primary agent of this and prior RSC recent efforts to embrace digital technology, as optimistically pronouncing, “No longer will we look at digital as ‘other’ but we will just go how are we going to do it?”[15] One can almost hear the wishful thinking of Ellis, who for years had likely been the primary person at the center of the RSC who did not view digital technology as “other.” However, the making-of videos suggest that the director, Doran, and several key actors, including Simon Russell Beale (Prospero) and Mark Quartley (Ariel), were not entirely convinced of Ellis’s position. Even as Doran, Beale, and Quartley express excitement about the technology, they betray plenty of suspicion as well. One of the videos, “Prospero Meets Ariel,” documents the first time Quartley and Beale worked with the Ariel avatar that The Imaginarium created and that would be rendered in real time on stage through Intel’s computing power. As Doran announces that it is the “first day when we bring technology and the actors, the sound department and all the amazing wizards from Imaginarium and Intel together,” the video soundtrack song sets the theme with its refrain about the challenges that the RSC’s human actors would encounter when working with complex technology: “And I try to work it out.” Quartley and Beale, like Doran, frame their relationship to the technology as something of a confrontation between the human actors and the nonhuman technological object. Beale worries about how he will get control over the technology: “It’s all very beautiful but I have no idea how we get to manipulate it and use it.”[16]

The tensions between the human actors and the digital technology coalesce most fully for Quartley, who has to figure out how to connect with his digital double. In the video, Quartley repeatedly describes himself and his avatar as totally separate beings, each of which relates differently to Prospero. He describes some of the frustrations he encounters as he tries to figure out his relationship with the avatar, and how that relationship may differ from Prospero’s relationship with it:

MARK QUARTLEY: We’re still trying to work out the dynamic, the relationship, between Prospero and Ariel and the avatar of Ariel, how that ménage à trois works. That’s a bit of a—a bit confusing at the moment. I think it’s getting clearer and clearer, the more we do it.

[MUSIC: “And I try to work it out . . .”]

QUARTLEY: I’m a bit tired now. It’s been a long day, energetic day, I feel like we’re really getting somewhere. I think we’ve cracked the way that I can visually have a relationship with Prospero at the same time as the avatar can.

Although Quartley’s confidence grows the more time he spends with his digital double, even after a long day of “try[ing] to work it out,” he continues to see a divide between his body and that of the avatar, two entities that can have an intimate “relationship” but are not integrated. Quartley has tried out a technology that challenges conventional ideas about human identity, but the video presents him leaving the studio that day feeling his human identity as unchanged and intact. He remains an autonomous self with fixed, stable boundaries.[17]

Quartley’s perspective on the avatar as an object totally separate from himself is partly a result of the RSC rehearsal process, which had Quartley meet his avatar the same day he met Beale. This set the conditions for Quartley to view the avatar as a third entity, a member of the “ménage à trois” on stage rather than an integrated part of his person. In contrast, when Saltz used mocap in his earlier production of The Tempest, his rehearsal process paved the way for a more integrated human–avatar experience. Saltz’s Ariel, played by actress Jennifer Snow, rehearsed extensively with Marshall Marden’s Prospero before the mocap technology was brought into their dynamic. Even more notably, when Snow rehearsed with Marden, she did not occupy the space her actual body would occupy during the production—a cage in the back of the stage; rather, she was positioned in the place her avatar would be during the show. Although Saltz does not discuss this decision in his article documenting the production, one might surmise that this rehearsal technique enabled Marden’s Prospero to see Ariel as an enmeshment of the digital avatar and human actor in addition to enabling Snow to connect more deeply with her avatar, even if only through her imagination. All of these factors would have forestalled the sense of alienation from the avatar that Quartley describes.

Quartley’s perspective on the avatar as an alien other was echoed by the rhetoric around technology used by the RSC and its partners at Intel, and even, surprisingly, by The Imaginarium. Since the entire business of the latter is focused on improving the responsivity of human actors and digital avatars, their staff were to a larger extent already cued into the enmeshment of human and digital worlds. And so it makes sense to hear Ben Lumsden, at the time Head of Studios for The Imaginarium, state in another promotional video entitled “The Tempest & Intel” that “the most exciting thing about what we’re doing at the moment is enabling an actor to have a real connection with an avatar,” an experience he says he facilitates in the studio all the time for films and video games.[18] Serkis, the company’s cofounder, also recognized the imbrication of actor and avatar. In the video “400 Years in the Making,” Serkis describes Quartley as “the marionette and the puppeteer at the same time.”[19] That said, spokespersons from The Imaginarium come across as intimidated by what Tawny Schlieski, Director of Research at Intel, describes as “big” technology. Lumsden remarks, “I’ve never seen technical setup like this. This place is full of huge amounts of technology, much more so than most film sets that we’re on.”[20] In interviews and promotional videos, RSC artists and Intel executives similarly tout Intel’s technological marvels, drawing out the Ariel avatar’s supernatural qualities and alien identity. They boast that animating the 336 joints of the Ariel avatar in real time requires 200,000 files running simultaneously, and that the computer is loaded with “50 million times more memory than the computer used for the moon landing”—a computer whose disconnection from and even antagonism toward its human actors is emphasized through its nickname, the “Big Beast.”[21]

The question on the minds of RSC creators and audiences alike was whether the beastly technology would overshadow or, worse, undermine the human actors trying to tell their story seamlessly and compellingly. Reviews were mixed on this count. One techie reviewer lamented the inclusion of digital technology, concluding that it interrupted the purity of theater: “The performance capture technology . . . jars slightly, as the spectacle and physicality of theatre is temporarily stilted by what felt to me like an unforgiving, cinematic interruption.”[22] But most reviewers were impressed and echoed the RSC’s public narrative. Michael Billington, for instance, raved that the performers, not the tech, were the stars of the show.[23] This is not to say, however, that the human actors were, in actuality, in charge. Ultimately, as the rehearsal and production process continued, Quartley’s autonomy as an actor was sacrificed to the demands of the digital system of which he was, necessarily, a part. To eliminate glitches in the motion-capture performance, Quartley had to learn to move differently, holding his head at angles different than what felt instinctual to him, changing the way he crouched down, and so forth. Pascale Aebischer’s analysis of show reports from the RSC reveals the degree to which Quartley and other “human actors . . . had to adapt their range of movements to fit in with the quite rigid demands of the technology,” suggesting the company’s emerging recognition of Quartley’s cyborgian identity.[24] But if Quartley’s body and his bodily habitus were altered by the technology, his attitude toward that technology was not similarly transformed. Quartley’s public statements continued to underscore a disconnect between his human body and that of the digital avatar, suggesting limits to the kind of posthuman integration that The Imaginarium may have imagined. In “400 Years in the Making,” Quartley shows that he continues to see his human body performance as separate from the avatar body created with digital technology. He marvels that audiences “get to see two fully fledged performances, one of which is an actor and another is this apparition that can fly around this space.”[25]

While backstage performance notes show Quartley submitting to the demands of the technology, changing the way he moves to appease the digital apparatus, the company’s public discourse around the production tells a different story: one where human actors do not submit to but master big tech, turning digital technology into a tool for their creative use. In one making-of video that is centrally about the collaboration with Intel, Stephen Brimson Lewis, Director of Design for the RSC, offers a reassuring comment: “It’s the creative process drives the technology [sic], not the other way around.”[26] The production’s creative artists repeat a similar idea in other public-relations materials. Beale, though awed by the beauty of the technology, remains stalwart until the end about the superior role human actors play. In an interview with the New York Times published in January 2017, he says, “I still believe the most important bit is the human interaction, but if that can be enhanced by technological means, then great.”[27] In the same New York Times article, Doran—responding to concerns that Intel was simply using the RSC and its formidable reputation to improve their own company’s brand—asserts, “They have their own agenda of how they want to extend and explore and advertise their technology. . . . But it’s serving our ends perfectly—we’ve used the technology to enhance the play, and we feel very proud of that.”[28] In promotional materials, Doran speaks often about the desire to create a sense of “wonder” for the audience, as is befitting The Tempest as a play, and he typically presents the RSC as the conceptual leaders of the collaboration. For example, in an interview included in “400 Years in the Making,” he relates how he educated “the guys at Intel” about the seventeenth-century masque tradition that, he explains, is key to The Tempest and a primary rationale for using digital technology in the first place. For Doran, the technologies Intel deployed are “tools,” even if “pretty spectacular tools.”[29]

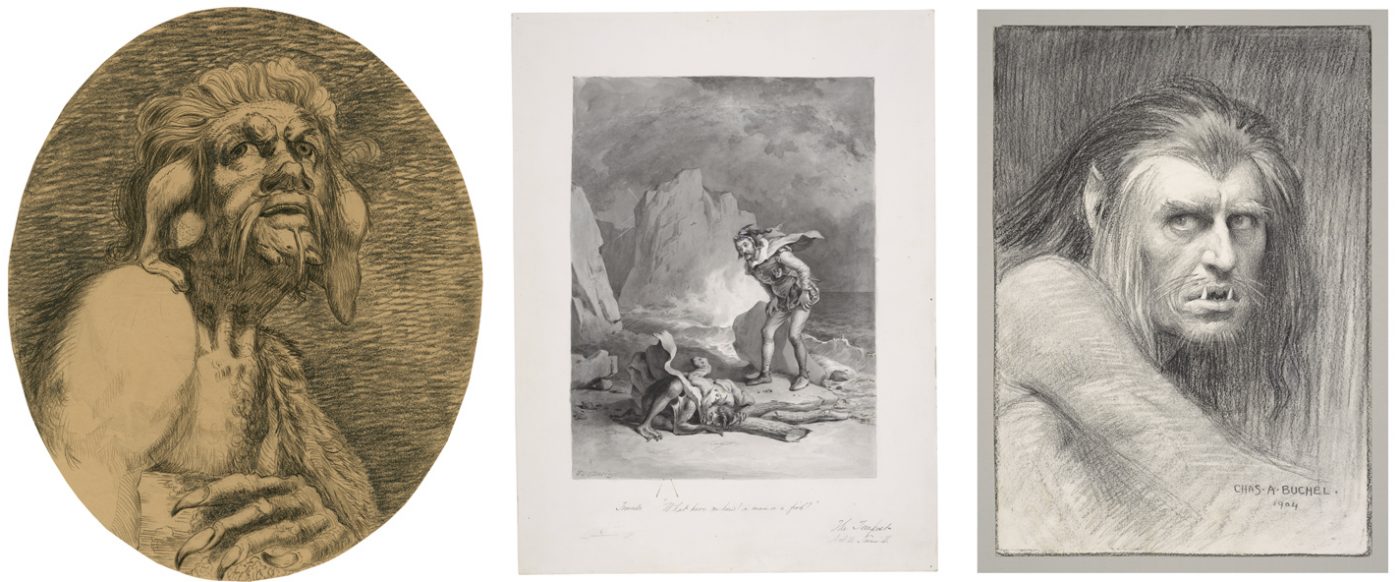

The RSC’s representation of digital technology as tool, as other, and, occasionally, as enemy is rather unfortunate. Virtual environments provide an ideal opportunity to abandon the liberal humanist desire to dominate our environment and instead approach the human body as part of a flexible and adaptive distributed system.[30] But the RSC’s perspective on digital otherness is not just a missed opportunity to engage more thoughtfully with digital technology in Shakespeare performance; it is an evasion of the ethical issues at the heart of the play that they used this technology to stage. Characterizations of Intel’s technology as the “Big Beast” are especially worth pause here given that the play staged with this technology, The Tempest, is about a white European man who secures his home on an exotic island by using magic to subdue the island’s one native inhabitant, Caliban, a character constantly described as less than human—and frequently staged in production history as part beast. From Prospero’s perspective, Caliban is something like a glitch: a noisy and unpredictable disruption in Prospero’s plan for mastery over the island’s inhabitants and visitors.

The RSC’s public narrative of the stalwart director, Doran, successfully conquering beastly technology uncomfortably mirrors Prospero’s own narrative of conquest, especially as it was told within the diegesis of this particular production. The RSC production sidesteps some of The Tempest’s most troubling ethical questions about turning other–and “othered”–beings into tools for human progress. Whether we read The Tempest as a parable of New World conquest, settler colonialism, or early modern race-making, the play has long troubled scholars and directors.[31] Prospero forces Ariel into servitude, insisting that Ariel execute task after task so as to enable Prospero to punish his enemies and maintain control over the island he has taken as his own. Further, Prospero uses his magic to enslave Caliban, the island’s one native inhabitant, forcing him to do menial work with no compensation and under great duress. Prospero tortures or threatens torture of Ariel and Caliban if they fail to do his bidding. All the while, he tries to manipulate his daughter Miranda into falling in love with a nobleman he has shipwrecked on the island with magic, all in a ploy to punish his enemies and reclaim his family’s place as European rulers. If earlier generations of readers and directors took pity on Prospero—an aging man who was wrongly displaced from power by a vindictive brother and exiled from his homeland with nothing but his books—few today can overlook his troubling treatment of Ariel and especially of Caliban. But that is precisely what the RSC does in its production. Reviewers describe Beale’s Prospero as “less . . . colonial tyrant than sorrowing mentor” to Caliban.[32] Beale’s Prospero does ultimately exhibit remorse, but not for his treatment of Caliban or Ariel—only for his treatment of his noble political enemies. The sympathetic portrayal of Prospero and emphasis on his humanity—one reviewer calls this “the most human, complex, and vulnerable Prospero I’ve ever seen”—though not unusual in the play’s long production history, is particularly noticeable in this case.[33] The last time Beale performed in The Tempest for the RSC was 25 years earlier, when he played Ariel. His Ariel had been righteously vengeful, his iconic gesture having been to spit in Prospero’s face when finally released from service. That anger, which highlighted the problem of forced servitude, is completely invisible in the Doran production, however.

Instead of grappling head on with The Tempest’s uncomfortable ethical dilemmas—how can we empathize with a protagonist who forces into servitude those he encounters on the island where he settles?—the RSC presents a metanarrative of its own capacity to master the alien other of digital technology. Instead of presenting Prospero as an ethically compromised conqueror of the island’s inhabitants, the RSC presents itself as a conqueror of technology, the beast that must be made to serve human will. Not surprisingly, reviewers who praised the production’s effective use of mocap technology frequently conflate the production’s director, Doran, with Prospero, representing both figures as triumphant in their quests to tame their beasts. As one reviewer writes, Doran “presses not just the sprites of the island but the wizardry of digital technology into Prospero’s power.”[34] As the RSC pursued the most “robust” avatar possible, all in the name of delivering consistent “quality” to audiences, it sought to display Doran’s mastery of technology and its own magical powers.[35] The RSC and Intel went to incredible lengths to ensure the spell would not be broken by glitchy animation. In this triumphal account of the play and of the relationship between humans and computers, there was no room for error, no room for glitches in the animation that would betray a human failure to master the digital other.

“This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine” | Play the Knave’s Glitchy Bodies

Given that the RSC’s production involved live motion-capture performance, there were bound to be some glitches on any particular night of the show. The point here is not to determine whether the company did ultimately master the technology. Rather we want to call attention to the rhetoric of mastery and the creative intention: to offer the illusion of magic for audiences by producing the most seamless animation possible. This aesthetic intention, we are arguing, has ethical implications, which become even more clear when we contrast the RSC’s motion-capture performance with that produced by players of Play the Knave. As we have shown in prior acts, Play the Knave lets the glitches remain and run wild: it stages rather than disguises the human failure to master a digital other. We would suggest that, just as Caliban serves as a constant reminder of Prospero’s ethical compromises, glitches in mocap can have a salutary function. They compel players to perceive digital technology as a partner with which to play rather than as an oppositional other they need to master.

Despite the major differences between the RSC’s production of The Tempest and Play the Knave, there are sound reasons to examine these projects alongside each other. In both cases, the mocap system was built to allow the human actor significant license over their avatar’s movements, which is not always the case in motion-capture experiences. For instance, in many of the Kinect-based dance games created for the Xbox gaming systems—such as Dance Central (2010, Harmonix)—the avatar moves independently on screen and the user’s engagement is limited to mimicking the avatar, with points scored whenever a particular joint on the player’s body matches the position of a point on the avatar. But in Play the Knave, as in the RSC production, the player’s movements are rendered in real time, allowing the player to shape the movement of the avatar directly. Additionally, in both our game and the RSC production, players/actors perform their scenes before live spectators who watch as the players use their bodies to animate the avatars. These are the conditions that create the risk the RSC worked so hard to eliminate in their production—a risk that Play the Knave cannot ever hope to eliminate. The reason our avatars glitch far more often than the RSC’s Ariel avatar does is because the RSC’s performance system is astronomically more complex and expensive than ours. Our players are not wearing special suits that would help a motion-capture camera to more reliably locate the joints of the player’s body as the joints change positions. Our game uses just one camera, whereas the RSC used 27. We run our game on a regular PC gaming computer—powerful, yes, but hardly a beast. Were Play the Knave to require the bespoke Intel equipment the RSC used, it would not be playable in classrooms, theater lobbies, museums, or living rooms.

We discussed the technical reasons for our glitchy avatars in Act IV. Here, we want to think instead about what is at stake in these glitches for players and audiences of The Tempest. We can start by observing that glitchy avatars look unnatural, indeed, monstrous: avatar hands and feet twitch and spin erratically; a hand penetrates through the stomach; an elbow contorts in an unseemly direction; a head sinks down inside the body; a body disappears entirely; and so forth. One can see why a company like the RSC would have been worried about glitches, which can be more disturbing in live mocap than in other modes of animation because of the relationship mocap sets up between human actor and digital avatar. When actors use their bodies to move their avatars, they are invited to feel an intimate, embodied connection with their digital doubles. The physical performing body melds with that of the avatar, producing a shared, distributed body that exists across and between screen and ambient space.[36] One reason for this is that, technically speaking, the body of the avatar is not materially distinct from that of the human controlling it. To understand this material imbrication, it helps to think about the difference between mocap and other technologies of visual capture, such as photography or film. In photography and film, the human actor’s body is translated into or represented through another form—redimensionalized, flattened, and rendered pure surface. By contrast, as Nicolas Salazar Sutil explains, mocap rendering works topologically—via mapping. So mocap does not leave behind the physical form of the encoded body.[37] While the physical performance data can certainly be reskinned in ways that disregard or whitewash embodied differences, its translations can also enable experimentation with alternative, distributed forms of embodiment.[38] Indeed, the meshing of the physical and the computational, meatspace and cyberspace, allows for players to develop a significant connection with their digital doubles. This connection can extend to audience members, as well.

The flip side is that disruptions or misalignments of the body-mapping process can sometimes trigger aversion, or what is known as the “uncanny valley” effect.[39] When an avatar mimes its human player closely but imperfectly—drawing attention to the intimate entanglement of the player and the apparatus while also revealing contradictions between the captured body data and the player’s own self-perception—it can create an uneasy feeling.[40] Many commercial games made for Kinect lessen the likelihood of discomfiting uncanniness by stripping the user of any actual responsibility for the actions of the avatar. In games like Dance Central, no matter what the user does, the screen presents a beautiful and perfect dancing body.[41] Play the Knave differs from these games in that, like the RSC’s production of The Tempest, it gives the player responsibility for the avatar. This design decision, combined with our lower-cost mocap system, means that the “monstrous” avatar body is allowed to display itself—and let its freak flag fly. Players believe they will experience what it is like to be Ariel, but they discover, instead, that they are Caliban.

The experience is akin to that of playing a “fumblecore” game—a genre of video games that intentionally introduce glitching, janky controls, floppy ragdoll physics, and other unruly mechanisms to disrupt the seamlessness of play and the user’s sense of mastery of the avatar.[42] Play the Knave accentuates this phenomenon because, whereas players of most fumblecore games can focus their discomfiture on a tangible device (mouse, keyboard, handheld controller) that mediates their relationship to the avatar, in live mocap the controller is the player’s body itself. When the player’s body serves as both actor and mediator, players feel more responsible for the avatar’s performance on screen. And here lies the ethical promise of glitchy mocap interfaces for Shakespeare performance.

Reflecting on her work using mocap performance, Susan Kozel writes, “When our data seems to perceive and act independently and at a distance from us, the composition and sanctity of the self is . . . called into question.”[43] As a performer invested in experimental art, Kozel can embrace glitchiness as a value in a way that conventional theater companies like the RSC presume they cannot. Recall that, for the RSC and its collaborators, “there’s no room for error.”[44] But the RSC’s insistence on displaying perfection and human mastery over technology in its productions is not an inevitable approach. It is a calculated and expensive decision about brand identity that underestimates what Shakespeare theater can do for its actors and audiences. In particular, glitchy mocap offers a unique opportunity to reflect on our relationships to our own bodies, particularly our expectations of normative beauty. Moreover, the glitchy interface of Play the Knave provides a natural opening for considering how hierarchies of all sorts operate in Shakespeare: hierarchies between men and women, masters and enslaved, and, yes, humans and technology.

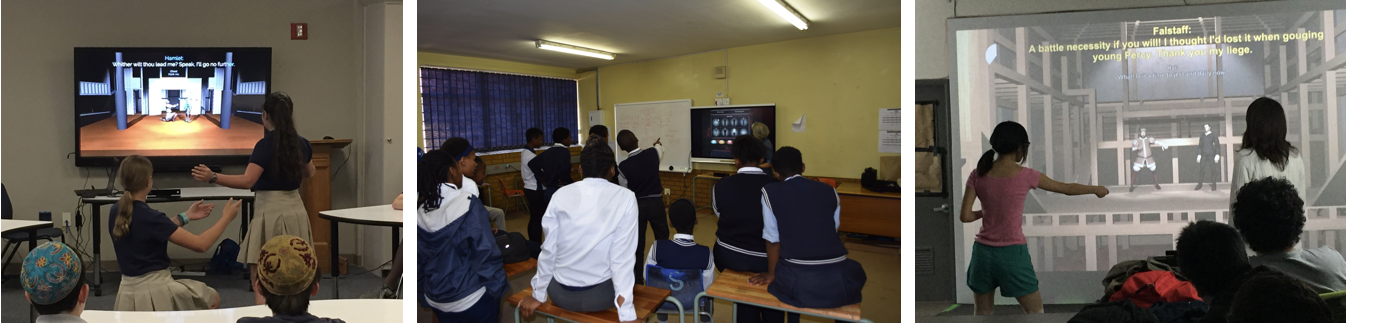

Our research on Play the Knave has revealed the promise of the glitchy interface for interrogating not only a range of different hierarchies, but the concept of embodiment as well. Through exhibitions of the game in museums, libraries, theater lobbies, and other cultural spaces, we have been able to examine firsthand how players interact with the game’s interface. More extensive data on player responses has come from implementations of the game in K–16 classrooms. The game has been used in over a dozen different classes at UC Davis since 2015. Since 2018, we have also run an outreach program to bring Play the Knave to classrooms across the U.S., offering teachers free loans of the equipment required to run the game. To date, around twenty schools have taken advantage of the loaner-kit program, with some participating for multiple years running. More recently, Bloom has undertaken a collaboration with Lauren Bates, a high school teacher in Cape Town, South Africa, to develop specialized lesson plans for Play the Knave that are focused on themes of violence in the plays, with hopes of helping teachers use their Shakespeare units to open up discussions with students about racial and gendered violence in South Africa today. The complete program, called “Blood Will Have Blood,” has been adapted for use in U.S. schools, as well (see Appendix).

We have only begun to analyze the data from the thousands of students who have experienced the game in classrooms, but our observations of players at public exhibitions and preliminary research findings about classroom experience reveal that the game’s glitchy avatars serve an important role.[45] For one thing, we have found that the glitches produce laughter, which felicitously destabilizes Shakespeare’s hierarchical authority. Nearly all the educators we have surveyed about their experiences teaching with the game have noted that the glitches produced, as one put it, “some fun moments and some giggles.” Another teacher observed that the “students thought it [the glitchy avatar] was hilarious.” Another appreciated how the laughter built a positive classroom community: the glitches “made it unintentionally hilarious from time to time, and it’s almost always good to laugh together, without laughing at a particular person.” Students have expressed similar sentiments when surveyed about their experiences with Play the Knave in class. Between November 2022 and June 2023, we administered one version of our survey at eleven different schools (seven high schools in the U.S., one high school in South Africa, two universities in the U.S., and one university in Taiwan), receiving 384 total responses.[46] Although our survey did not inquire directly about the glitchiness of the avatars, many students spontaneously brought up glitchiness in the open-ended questions at the end of the survey.[47] Among the students who answered these open-ended questions, about 25% of them made comments about avatar glitchiness. About a third of these respondents discussed glitches positively; examples of comments included: “It was funny when the characters glitched and it would make people laugh”; “It was enjoyable how they would sometimes glitch and make the movements funnier”; “I love how the avatars phased through the ground, started violently shaking, and crumpled up into a ball. It’s the best game I’ve ever played”; and “The models would clip in and out, people would often laugh at the sight of it in the classroom . . . I definitely hope for this to remain.” A third of the respondents discussed glitches negatively, especially in response to the question, “Is there anything else you would like to share about your experience with Play the Knave.” Students took this opportunity to advise us on ways to improve the game, making comments such: “I found the avatars cool because they moved, even though it kept glitching”; “it was glitchy but its [sic] still cool”; “it needs a little more work like not glitching”; “fix the bugs when interacting with the avatars.” For the final third of respondents who mentioned glitches, it wasn’t clear whether these were a feature or a problem.[48]

Whatever their declared view on the glitches, the students who pointed out the glitchiness of the avatars overwhelmingly reported tremendous enjoyment of Play the Knave, with 88.4% of them agreeing to some extent with the statement “I had fun playing and/or watching the game,” which is just slightly higher than the number of students who expressed similar levels of enjoyment but did not say anything about the glitches.[49] Although this limited data does not prove that glitchiness contributed directly to students’ enjoyment of the gaming activity, it does clearly suggest that the glitches did not detract from their perception of the Shakespeare lesson as fun.

It is notable that so many students have reported having fun during Play the Knave lessons. Teachers have often remarked to us that it is rare for students to express enjoyment, let alone laughter, when they are learning Shakespeare. When we asked teachers about examples of student learning from the Knave activity, one pointed directly to the pedagogical importance of creating a fun, playful classroom mood: “[Play the Knave] made my students lighten up and become more comfortable with the language of Shakespeare, and most importantly giggle and have fun!” Another teacher was surprised to find how the hilarity of the glitchy avatars kept students engaged, even those not performing: “The students not doing acting were also engaged. They found it great fun to watch groups’ misadventures with the avatars.” One reason this laughter is notable to teachers is because Shakespeare tends to strike fear in most students, who are intimidated by the language and by Shakespeare’s reputation. The glitchy avatars help counter Shakespeare’s outsized authority. Such destabilization is more critical than ever in light of calls to decolonize the classroom, displacing Shakespeare to make room for texts by women and writers of color. The inclusion of more diverse writers is certainly a worthy undertaking, but decolonizing the classroom is not just a matter of replacing Shakespeare; any writer can be taught in a way that upholds colonialist principles. It is the hierarchical way in which Shakespeare is often taught that perpetuates his part in colonialist oppressive structures.[50] Teachers, challenged by Shakespeare’s language and students’ resistance to it, sometimes fall back on more conservative teaching strategies—such as lecturing about the meaning of the plays—in hopes of keeping students engaged. Our research has shown that glitches help to break down students’ sense of intimidation in the face of Shakespeare, lightening up the classroom atmosphere and the pressure on teachers. When the glitches show up—and they always do—Shakespeare inevitably gets knocked off his venerable pedestal.

Whether in the classroom or in public contexts where we have installed the game, we have found that some of the pleasure for players comes from experimenting with the glitches. This playfulness is especially evident when children engage with the game. For example, at our exhibition for Shakespeare 400 in Chicago in 2016, there happened to be quite a number of children present. Some of the children were tickled to discover that, if they moved their bodies in a certain way, they could get the avatar dresses to fly up. So while one more serious child read the language on screen, the other worked on this Marilyn Monroe move.

The glitchiness of the avatars is not just a source of humor; it also levels the playing field for actors, in effect democratizing Shakespeare performance. When performing Shakespeare via Play the Knave, professional actors, with their seriousness of purpose and their expertise, are no more effective in creating a great performance on screen than are novices who have never acted before. In fact, as we have shown in Act II, professional actors tend to be less effective because their training has conditioned them to pursue smaller, more subtle movements that the Kinect motion-sensing camera fails to pick up. As a result, at best their avatars are more static; more often, these actors’ tendency to turn toward a scene partner or to gesture with their hands results in extreme glitchiness in the avatars—which, though quite funny for audiences, is not always so humorously received by actors who take their performances seriously. In contrast, players who “ham it up” using exaggerated gestures and improvise in response to any wild glitches that appear, welcoming the strangeness of these strange bedfellows, usually produce more impactful and interesting performances—and everyone has more fun.

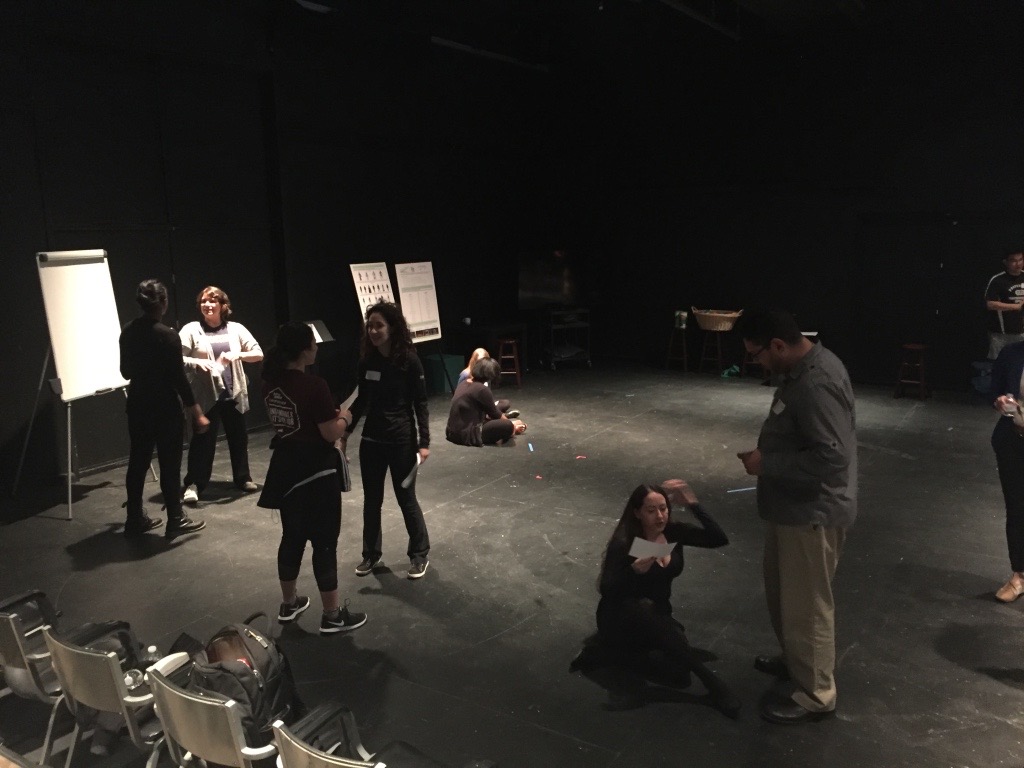

In effect, the glitches become invitations to collaborate with the gaming system. They provoke what Andrew Pickering describes as a “dialectic of resistance and accommodation” between human players and the nonhuman machine, leading players to conceive of their avatars not as inferior objects that do the bidding of their human masters, but as necessary partners.[51] One particular installation serves as an illustrative final example, in part because it focused on The Tempest. The installation was part of a full-day workshop on performance-based techniques for teaching Shakespeare at the university level, a collaboration with Shakespeare scholar–teachers from several institutions.[52] A mix of English majors and theater majors spent the day delving deeply into The Tempest’s themes and characters by way of different performance approaches, including groups staging interpretations of scenes in which Prospero engages with Ariel and Caliban. As the culminating activity, groups performed these scenes via Play the Knave. Many of the workshop activities that preceded the Play the Knave component emphasized self-discovery and, as is generally true of much theater-based teaching, tried to get students to connect more deeply with their bodies so that they could use their bodies and embodied voices as expressive vehicles for conveying their interpretations of the text. By the time students came to Play the Knave, they had established movement patterns and voice pacing for particular characters in the scenes from The Tempest that they were studying.

Play the Knave threw a wrench into their plans. Students felt they had achieved some mastery of Shakespeare’s text and their own bodies, but when they faced the screen, they were forced to take on a new scene partner, a digital interface that constrained their performance options and sense of personal expression. Some students were frustrated, but others saw this constraint as an opportunity. They improvised, trying out different sorts of bodily movements that the motion sensor could better understand, or they simply laughed at their failures to achieve a seamless animation.[53] In short, they approached the interface with a ludic spirit, often privileging play as a process over the play as a product.

At the workshop, this playful engagement with the digital platform opened up a rich conversation among students not only about theatrical performance (the relationship of director to actor, the function of improvisation, the value of playful experimentation), but about The Tempest itself, a play that has often been read as a metaphor for the theater. Even more to the point, as decades of anticolonial and postcolonial readings of The Tempest have shown, the play showcases the violence inherent in treating others as one’s tools. That violence is not only represented through the play’s narrative, but works at the level of performance, replicated in the rhetoric that directors and actors, such as those from the RSC, often use when they reflect on their relationship to theatrical technologies, digital and otherwise. Prospero imagines himself as a supreme leader who must grapple with recalcitrant underlings: an enslaved person who revolts, a servant who constantly asks for his freedom, a daughter who pursues her own romantic attachments. Avatars in live mocap are similarly untamable. Their glitches, like Caliban’s acts of resistance to Prospero’s white European supremacy, underscore the limitations of human control.

At the workshop, Play the Knave’s glitches helped open up conversations about the colonialist dynamics in the play, enabling students to move past overdetermined formulations of colonizer and colonized. In working with their avatars, students discovered that the act of controlling another entity creates a bond with that entity, and this interdependence can undermine hierarchies. Who controls whom? To be sure, one doesn’t need gaming technology to arrive at such a reading of The Tempest. But perhaps particularly for students, or indeed anyone who believes themselves to be politically enlightened about social, ethnic, racial, and gender hierarchies, there is something to be gained through embodied, play-based experience with a hierarchy less often questioned: the relationship between human and machine.

At the end of The Tempest, Prospero reluctantly accepts responsibility for and a kinship with Caliban—a being he regards as a nonhuman “thing”: “This thing of darkness I / Acknowledge mine” (5.1.330-31). In much this way, Play the Knave’s players, through the process of play, acknowledge kinship with and responsibility for the avatar bodies that are, but also are not, their own. The stakes here extend well beyond a reading of The Tempest. As users of Play the Knave discover the limits of their bodily autonomy and try to collaborate with instead of simply controlling a digital other, they must set aside liberal humanist values of self-empowerment. Some come to practice understanding for an entity with whom they have very little in common, but at the very least, Play the Knave’s glitchy interface reminds players of their responsibility for producing semiotic meaning, which is possible only if players adapt to the needs of the machine. To achieve a smoother animation, the player essentially has to empathize with the machine—understanding how it reads the human body—and then to adjust their physical movement so as to be more easily legible. Significantly, there is usually a tradeoff in the aesthetics of the resulting performance: to achieve an animation that looks more seamless, human actors need to undertake a physical performance that looks more glitchy. Or, to put this differently, for the animated digital avatar to look more human, the human actor has to be willing to look a little more monstrous. As players recalibrate their aesthetic standards, they engage in important ethical work that, as we have argued, the RSC’s production of The Tempest evades.

In their work on glitches, the game studies scholars Naomi Clark and Merritt Kopas write that “glitches are a kind of queer failure that we should celebrate; the failure that’s too drastic and uncontrolled for the orthodox notion of ‘try again and get stronger’ gameplay.”[54] The same could be said for Shakespeare performance. The RSC, like some other mainstream Shakespeare theaters, pursues cinema-quality graphics to amaze audiences, much like gaming companies that invest heavily in the best graphical displays for their video games. But much is lost when we try to bring cinema-quality graphics into the theater and into games, and when we treat theater audiences and gameplayers like moviegoers. Stunning graphics may impress us, but they move us far away from the interactive and risky pleasures that have always been at the heart of gaming and of theater. When Shakespeare ends The Tempest with a chess game, he reminds actors and audiences that games and theater are, at their core, forms of play, no matter what technology we bring into them.

These sorts of adaptations/adjustments extended to their vocal work as well, since the game’s karaoke interface mediates players’ vocal performances as well as their bodily movements. Players who ignored the karaoke interface sometimes ended up with awkward silences because they finished a line well before it disappeared from the screen. Those who adapted to the interface would slow down or speed up their recitation pace as they recognized the system’s timing. Some came up with strategies for dealing with any misalignment between their own desires and the workings of the system. For instance, while they waited for the next line to appear, they would ad lib some dialogue or perform some gesture or action that emphasized the line they had spoken.

Gorton, Space to Play, 38.

Billington, “The Tempest Review.”

Billington, “The Tempest Review.”

Gorton, Space to Play, 38.

Gorton, Space to Play, 38.

Billington, “The Tempest Review.”

Gorton, Space to Play, 38.

Catherine Mallyon, “Forward,” in Gorton, Space to Play, 4.

Catherine Mallyon, “Forward,” in Gorton, Space to Play, 4.

Catherine Mallyon, “Forward,” in Gorton, Space to Play, 4.

Catherine Mallyon, “Forward,” in Gorton, Space to Play, 4.

Catherine Mallyon, “Forward,” in Gorton, Space to Play, 4.

This production of The Tempest opened in November 2016 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon, and then moved to the Barbican on June 30, 2017. The RSC also released a filmed version of the production on DVD in 2017 as part of the “Live From Stratford-upon-Avon” series.

This production of The Tempest opened in November 2016 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon, and then moved to the Barbican on June 30, 2017. The RSC also released a filmed version of the production on DVD in 2017 as part of the “Live From Stratford-upon-Avon” series.

This production of The Tempest opened in November 2016 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon, and then moved to the Barbican on June 30, 2017. The RSC also released a filmed version of the production on DVD in 2017 as part of the “Live From Stratford-upon-Avon” series.

This production of The Tempest opened in November 2016 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon, and then moved to the Barbican on June 30, 2017. The RSC also released a filmed version of the production on DVD in 2017 as part of the “Live From Stratford-upon-Avon” series.

This production of The Tempest opened in November 2016 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon, and then moved to the Barbican on June 30, 2017. The RSC also released a filmed version of the production on DVD in 2017 as part of the “Live From Stratford-upon-Avon” series.

Billington, “The Tempest Review.”

Billington, “The Tempest Review.”

These sorts of adaptations/adjustments extended to their vocal work as well, since the game’s karaoke interface mediates players’ vocal performances as well as their bodily movements. Players who ignored the karaoke interface sometimes ended up with awkward silences because they finished a line well before it disappeared from the screen. Those who adapted to the interface would slow down or speed up their recitation pace as they recognized the system’s timing. Some came up with strategies for dealing with any misalignment between their own desires and the workings of the system. For instance, while they waited for the next line to appear, they would ad lib some dialogue or perform some gesture or action that emphasized the line they had spoken.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Billington, “The Tempest Review.”

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Sutil, Motion and Representation, 202.

Some key scholarship on these topics includes P. Brown, “‘This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine’”; Cartelli, “Prospero in Africa”; D. Willis, “Shakespeare’s Tempest and the Discourse of Colonialism”; Hall, Things of Darkness; Loomba and Orkin, “‘This Tunis, sir, was Carthage’”; Skura, “Discourse and the Individual”; Loomba, Shakespeare, Race, and Colonialism, esp. “Conclusion”; Barker and Hulme, “Nymphs and Reapers Heavily Vanish”; Kastan, “‘The Duke of Milan / And His Brave Son’”; Akhimie, Shakespeare and the Cultivation of Difference, esp. Ch. 4; Singh, Shakespeare and Postcolonial Theory; Espinosa, Shakespeare on the Shades of Racism, esp. Ch. 5; and Ndiaye, Scripts of Blackness.

Some key scholarship on these topics includes P. Brown, “‘This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine’”; Cartelli, “Prospero in Africa”; D. Willis, “Shakespeare’s Tempest and the Discourse of Colonialism”; Hall, Things of Darkness; Loomba and Orkin, “‘This Tunis, sir, was Carthage’”; Skura, “Discourse and the Individual”; Loomba, Shakespeare, Race, and Colonialism, esp. “Conclusion”; Barker and Hulme, “Nymphs and Reapers Heavily Vanish”; Kastan, “‘The Duke of Milan / And His Brave Son’”; Akhimie, Shakespeare and the Cultivation of Difference, esp. Ch. 4; Singh, Shakespeare and Postcolonial Theory; Espinosa, Shakespeare on the Shades of Racism, esp. Ch. 5; and Ndiaye, Scripts of Blackness.

Billington, “The Tempest Review.”

Billington, “The Tempest Review.”

This production of The Tempest opened in November 2016 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon, and then moved to the Barbican on June 30, 2017. The RSC also released a filmed version of the production on DVD in 2017 as part of the “Live From Stratford-upon-Avon” series.